TOC vs Lean - An Uneven Comparison

- Oct 15, 2020

- 18 min read

Want to read the Italian version? Click here

These days I have been involved in a very interesting thread by Anil Dosi (here the link) https://www.linkedin.com/posts/anil-dosi-jain-00aa619_when-wip-goes-up-lead-time-goes-up-quality-activity-6717597072545107968-Pnnf, who quickly illustrated the negative effects of high levels of WIP on lead times, quality, customer service and cash-to-cash cycle time.

As usual, the debate was split between fierce supporters of the supremacy of TOC (Theory of Constraints) and passionate supporters of Lean supremacy

In this article I explain how the discussion, whether it is more effective to adopt TOC or Lean to optimize the flow, is very often misplaced if not completely sterile. First of all because it is always necessary to refer to the characteristics of the productive environment, but not only. I do not want to share my conclusions now, read the article and you will discover "the assassin" at the end from the clues left here and there.

The Foundations of Theory of Constraints (TOC)

The Theory of Constraints, for brevity TOC, is a Scientific Managerial Theory; scientific, because TOC is developed by applying the principles of the third stage of science, that of the study of Effect-Cause-Effect relations (the first two stages are classification and correlation).

TOC moves its steps from some core observations:

Organizations are complex systems characterized by interdependency and variability between the parts they are composed (resources and processes).

To understand and manage complexity, we shall focus on the relationship and interdependencies between the parts: performance are not additive

In such connected system, performance are dictated and limited by the resources with less capacity: their Constraints

To maximize performance of the system, we need to exploit and get maximum value out of the constraint. As a corollary, by increasing the performance of "non-constrained" resources we can get only marginal productivity gains

It is a proof that, very often, enormous investments, when they are not focused on the real constraint of the system, bring in to small/null benefits to the bottom line: raise the hand whoever has seen millions of euro invested into a new ERP, and has found himself by miracle with 50% less in inventory, improved service levels of 50% and increased profits of 30% in 6 months.....I see few hands raised...

The primary objective of TOC is to maximize the productivity of the system, i.e. the ability of the system to generate Goal Units, which in TOC is called Throughput.

Speaking of a profit-oriented organization, The Goal is to make more money now and in the future, and therefore productivity is measured in terms of money generated, real cash flow. Under an accounting point of view, Throughput - or "Throughput Margin" - is measured as the difference between Revenues and Totally Variable Costs.

You should not confuse Throughput with the following concepts:

The Added Value, to which we are accustomed from the schemes of the P&L defined in the IV EEC Directive, as to define the value of production it adds to the revenues also the variation in inventory. According to the principles of Throughput Accounting, in the definition of Throughput, the inventory of finished and semi-finished products - moreover valued only at the purchase price of direct materials - are not considered as value. The production of inventory is considered as a "liability" as well as for the Lean (even if we book them in the Asset side of the Balance Sheet)

The Gross Margin that we are accustomed to use in the management reporting schemes based on Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) . In cost accounting, in fact, the cost of sales is determined adding not only the cost of materials, but also the absorptions of part of the operating expenses (direct labor and factory overhead). In Throughput Accounting those fixed costs are completely considered as Operating Expenses of the period and absolutely not allocated to inventory, and thus to any kind of COGS, that in TOC and Throughput Accounting is something that really doesn't make any logical sense.

According to the TOC definition of the Goal, productivity, of a production site for example, is therefore not measured in terms of its ability to produce output (products) from the resources employed, but as the ability to produce Throughput, i.e. the difference between revenues and variable costs incurred to produce, market and distribute the products sold. For example, a plant with a world class OEE, let's say 85%, could be highly unproductive according to TOC principles if all the products released were unsold and destined exclusively to the bins of the warehouse. The Throughput Margin would in fact be zero.

After this clarification, and starting from the primary Goal, TOC has developed a simple management algorithm in five steps (Five Focusing Steps).

Identify (or strategically position) the system constraint

Exploit the constraint, maximizing its performance and ensuring that no unit of its available time is wasted (wasted not producing items that are in demand, or wasted producing inventory)

Subordinate everything else to the above decision

Elevate the constraint, if the previous steps are not enough (e.g. to meet unsatisfied demand)

If in the previous step a constraint is broken, start again. Warning: don't allow inertia be the system constraint (a call to action to Continuous Improvement)

The Five Focusing Steps represent the architrave from which the different operating algorithms developed by TOC stem. Among these, we will compare the DBR (Drum-Buffer-Rope) logic for production scheduling and control with the logic of Kanban System developed by Lean, from which we will draw our conclusions.

The Foundations of Lean

Lean Manufacturing, but in my opinion it would be more appropriate to talk about TPS - Toyota Production System, is a model of managing production based on the following principles:

The ultimate goal of the company is to maximize Value

The system generates value when the Customer is willing to pay a price for the system output

The processes for which the final customer is not willing to recognize a price, do not generate value and are considered waste to be eliminated.

Starting from this definition of value, Lean has developed its operating procedures, such as the House of Quality used in the product design phase to trace the elements that create value for the customer, or the famous 5s, or the Heijunka scheduling and the Kanban System.

If the main objective is to create value and reduce waste, why so much attention to the flow of production? The following diagram explains it.

In a manufacturing environment, touch time (or Run Time) , i.e. the time in which operations are carried out, is typically much less than the queue and waiting time between operations. In job shop environments, interoperation times represent the largest share of manufacturing lead time. Queue times are generated because resources are not immediately available to perform the required operations. In these times WIP, i.e. inventory waiting to be processed, one of the main forms of waste, tends to accumulate. Thus, the importance and focus of Lean on the flow to reduce waste of time, which generates unwanted inventory and slows down the process of order fulfillment, creating customer dissatisfaction.

Comparing TOC and Lean

Let us now begin the comparison, taking as a reference a profit-oriented manufacturing company.

Comparing the respective Goals

To understand the TOC definition of the Goal, we must formally explain the three key indicators to measure a company's performance:

Throughput (T) = the money that the company is able to generate through sales. Measured as Revenues less Totally Variable Costs

Inventory (I) = the money the company spends to buy the things it intends to sell. In other words, the inventory is valued at the purchasing cost of the aterials, without allocating the cost of transformation.

Operating Expenses (OE) = the money the company spends to transform inventory into Throughput, i.e. all production capacity costs (which are not allocated as transformation costs) and the remaining operating costs typically classified as SG&A

The Goal of TOC, we repeat, is to make more money now and in the future. This objective is achieved by creating a situation in which Throughput Velocity is higher than velocity of OE. Being OE substantially fixed, the pace of flow is core: if we maximize flow, we maximize Throughput and then we maximize Profit.

The goal of Lean is to Maximize Value: because value is created when the customer is willing to pay a price, and if to create value you need to eliminate waste, it is quite intuitive to argue that maximizing value implicitly is a functional goal to increase profits.

Well, we can therefore argue that the objectives substantially coincide, although:

TOC Goal is much more "explicit"

TOC has created tremendous value, by re-defining how to measure the system performance and local decision impact toward the Goal with Throughput Accounting, something that Lean has not stressed enough the importance

There is a formal difference in "accents" that we explain better afterwards.

Let's go further.

Let's compare the two methods: how to reach The Goal with TOC

If the goal is to make profits, and since operating expenses are substantially fixed, it is obvious that the number one measure, the goal to maximize, is Throughput, and it is obvious that this goal is achieved by maximizing and controlling the flow: the faster the company is able to transform materials into products to sell, the greater the Throughput generated over the period of time.

TOC, explains, moreover, that the rate at which the system is able to produce Throughput per unit of time (Throughput Velocity) is dictated by the constraint. For this reason, in its algorithm to regulate flow, TOC focuses on the exploitation of the constraint. In production, the algorithm developed by TOC to control flow and exploit the constraint is called Drum-Buffer-Rope, and the flow control model is called Buffer Management.

Let's explain the two concepts.

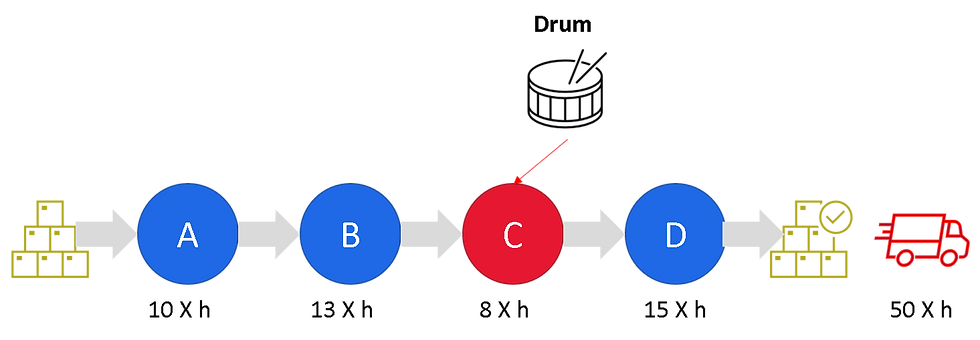

The Drum, is the pace at which the system can / must produce to meet demand. Let's imagine we have four resources with the average hourly output capacities shown in the graph below (10 units per hour for A, 13 units per hour for B, etc.)

Let's assume that the average market demand is 10 units per hour: no matter how hard we try, the above system, on average, can not produce more than 8 units per hour, with the rhythm of the production flow determined by the resource "C", the constraint and drum of the system. Since every single second of use of C can be sold on the market, the goal is to keep C fully productive, limiting any waste of its time as every minute wasted would represent a loss of Throughput.

The Buffer is the mechanism to protect the constraint, and therefore the flow, from statistical variation and Murphy. TOC uses an extremely elegant mechanism, the concept of Time Buffer, i.e. an advance of time with which to schedule the release of materials at gateway operations, to ensure that they reach the constraint in time. Why time and not physical stock? Because in fact - when we talk about materials - the effect is the same: releasing the materials in advance means to make them arrive, on average, with a certain advance, thus creating a safety to protect the constraint. Finally, time also makes the model extremely flexible to be applied to regulate any type of process, even pure services.

Using a time concept, the control is focused not on measuring "how much material do we have available at the constraint", but "how many orders are at risk for arriving late to the constraint". This control is called buffer management, and is implemented by dividing the time buffer into three zones plus one:

The Green Zone, are the orders that arrive at the constraint with adequate advance

The Yellow Zone, is the range in which most tasks from upstream processes are expected to arrive at the constraint.

The Red Zone, are the orders that have not yet reached the constraint and that have already consumed most of the time buffer, in other words the orders that risk arriving late and that must therefore be closely monitored and eventually expedited

The Black Zone, finally, includes the orders that have not reached the constraint and that have consumed all the time buffer and are therefore late.

Finally, we have the Rope, which is the flow of information that, starting from the scheduled operations at the constraint, determines the dates, a time buffer ahead, to release materials to the gateway operations. The Rope is not a "rigid" scheduling, it basically informs the gateway operations that they can start working when they have the material available, but "not before", where the cut-off date "not before" is determined by the expected date of arrival at the constraint by subtracting the time buffer.

Considering more complex routings, the DBR system places additional buffers also downstream of the constraint, as the goal is to protect the constraint not only before, but also not to waste the output of the constraint after, in the subsequent downstream operations. Technically the buffers are positioned at the shipping point, to protect the market and deliveries, and at the convergence points of routings that do not pass through the constraint, to avoid that the semi-finished products processed by the constraint wait unnecessarily for the other components.

There is also a simplified version, called S-DBR, but for the purposes of our comparison it is not necessary to add other variables to the discussion.

Summarizing:

We have a production scheduling model that, first of all, tries to maximize the productivity of the system by maximizing the flow through its constraint

As the goal is to maximize throughput, we schedule orders that are in demand - and not for inventory production. So we have a clear pull model.

Protection of the flow from variability and Murphy is done through the time buffer and with the protective capacity maintained on non-constrained resources.

The Rope is the mechanism that subordinates the scheduling of other resources to the constraint, informing these resources to "refrain" from producing before the date determined by the time buffer, thus preventing the release of materials before that date, to avoid accumulation of WIP, that causes longer queues and higher probability of non instant availability of resources

Let's compare the two methods: how to reach The Goal with Lean

According to Lean principles, the goal of maximizing value is achieved by eliminating waste for which the customer is unwilling to pay a price.

In the Lean philosophy we talk about 7 (+1) forms of waste, called Muda, illustrated below.

In order to eliminate waste, T. Ohno - the father of TPS - sensed that the goal had to be achieved through optimization and flow control in order to:

produce exactly what and how much is in demand (pull production)

avoid producing if there is no demand so as not to generate overproduction and excess inventory

avoid releasing too much WIP in the system.

The mechanism implemented by Ohno to achieve this goal is based on:

Heijunka Scheduling (also translated mixed model scheduling): the basic principle is a form of production leveling in small batches, aligned to the actual demand rate, where production and mix volumes are balanced over time.

The production rate at the basis of scheduling is set by Takt Time, which is the production rate that must be maintained to meet demand.

Operationally, the flow is managed through the Kanban System and Supermarket.

The Supermarket is the inventory placed in strategic stages to decouple cells and is used to protect the flow

Kanban are the signals that are released to authorize work at the upstream work cell when a downstream cell picks material from the supermarket.

In other words, Lean manages the flow:

setting the production pace according to takt time

controlling the release of materials through kanban signals

protecting the flow with supermarkets, accumulations of WIP and materials between the various work cells, so that the cells do not find themselves starving for materials

adjusting the maximum amount of stocks that can be accumulated in the system (through the number of available bins)

Summarizing: what do TOC and Lean have in common and differences

Drawing the first conclusions, it would seem, that Lean and TOC, more or less, adopt the same principles.

Indicatively same goal: create more value (....to create more profit) for Lean. Create more profit now and in the future for TOC. Let's say that TOC provides a straight forward and ultimate goal; Lean provide a "means" to the Goal.

Same operating principles: to create value and therefore Throughput, you need to optimize flow and avoid excess production and unnecessary inventory

The package of operating mechanisms to schedule and control flow that implement the operating principle are conceptually similar

Both TOC and Lean set and control the pace of flow

On the pace of the constraint, with the Drum, or on the rhythm of the demand with the Takt Time. If we think a bit more about that: what happens, for example, if in our Lean environment the overall capacity of the system is lower than demand? Who would dictate the pace? The capacity constraint of course. So from this point of view we can say that - let's call it Takt Time or let's call it Drum - the pace of the flow is always dictated by the constraint:

a constraint that identifies in the market demand, when it is lower than the capacity of the system; or

a constraint that identifies with the internal resource with lowest capacity when the market demand exceeds the overall capacity

Both TOC e Lean protect flow from Variability and Murphy

The objective of supermarket is nothing more, nothing less than the objective of our TOC time buffer, an advance of material availability. The Lean Supermarket is in fact fed with materials produced in advance of actual consumption requirements, i.e. released a certain "buffer time" in advance of requirements.

Both TOC e Lean control the release of materials to shop floor.

Lean controls the release of materials and work permissions via kanban signals.

The TOC Rope informs the upstream resources not to process the materials before the date set by the time buffer. In other words, it is like creating a list of future planned kanban against the planned operations at the constraint: "if the order must reach the constraint on day x, do not start processing the material before the day x-buffer time".

Both TOC e Lean subordinate other resources to the constraint.

Let's explain the concept of subordination. According to TOC jargon, subordinate means that all other resources adapt their pace of work to the paced dictated by the constraint:

they are activated if and only if it is necessary to feed the constraint

they are activate at a time that is necessary to meet the required dates of the constraint, and not to optimize the non constraint schedule

if there is no demand from constraint, they refrain from producing.

Once the priority to maximize the productivity of the constraint is set, the productivity of the other resources becomes a secondary objective, subordinated precisely to the constraint.

TOC implements the subordination mechanism through the Rope, which defines the dates before which it is not allowed to start working.

The subordination mechanism, central and explicitly stated in the Five Focusing Steps, is not as explicit in Lean. Although not explicit, it is anyhow implemented implicitly through the kanban system: since the flow of material is dictated by the constraint, automatically the kanban flow is dictated by the constraint itself, and the other resources, adapting to this flow, are implicitly subordinating themselves to this pace.

Conclusions

It would seem that both Lean and TOC suggest we do the same thing, albeit in different terms. Some say they are "cousins". With a superficial analysis, one might be tempted to say that TOC copied from Lean (TPS was in fact born years earlier than TOC). But in reality this is not the case.

It is a matter of purpose: two different plans

When E. Goldratt conceived TOC, he aimed to create a Scientific Managerial Theory. For the purpose, It was necessary to "clean" the core concepts from any practical declensions, to find a universal principle that could work regardless of the specific operational context, abstracting from practical use cases.

This is the reason why introducing the "time-buffer", a holistic concept that can be applied both to a physical production of goods and to an immaterial production of services.

This is the reason of the importance of researching and explaining the limiting factor, the constraints, "the object" around which designing the theory. There is no trace about constraints in the Lean method, but not because in a Lean environment - no matter how hard we try to standardize and balance resources - constraints magically disappear. Constraints, whether market or capacity, unfortunately - or better, fortunately - exist for everyone: having knowledge of them, or choosing them strategically, helps to have a greater understanding of the system and helps to focus managerial attention.

This is why the importance and explanation of the mechanism of subordination, a concept that again is only implicit in Lean, but which in TOC takes on the utmost importance: you cannot reach the maximum exploitation of the constraint without activating the subordination of all other resources to it. It is a principle of coherence, as well as factual to really get the most out of our constraint.

TOC did not provide us with every operational procedure: for example, it did not teach us how to reduce variability (by the way for this there is the huge work of Deming), but it left us a much more important legacy: the very basic and most intimate rules, the management algorithm from which we can derive all the operational solutions we need to implement.

Lean, with its Kanban System, has provided us with "a possible procedural declination, implemented with physical operational tools of the axioms defined later by TOC to regulate the flow".

The different purposes, from which a different level of abstraction stem, is the very reason why I think it's completely inappropriate to make any comparisons between Lean and TOC to say which one is better to improve flow. We cannot compare a procedure with the Scientific Management Theory that sets the universally applicable rules that the procedure applies to a specific context.

We have just demonstrated that with TOC algorithm we can fully explain the mechanism of Lean, just as we can explain the strategy of a cycling team engaged in a team time trial for instance.

By the way, when MR. Ohno developed his TPS, he had no ambition to derive a holistic managerial doctrine for every industry: let's say he was "happy enough" to find an operational model that would work sufficiently well for his company. This does not mean that Mr. Ohno was not a genius, as he was able to design a practical operating procedure that applied scientific criteria not yet postulated and disclosed!!!. Chapeau.

Limitations of Lean procedures

Ohno has designed and implemented a production control procedure aimed at optimizing the flow and reducing waste (given the scarcity of resources in Japan at the end of WWII and the impossibility to use the expensive lines implemented by Ford to control the flow) and that would suit the specific characteristics of the production environment:

medium-low variety of products, with medium-high volumes

relatively stable demand

relatively stable and predetermined work cycles

relatively long product life cycle

In this context, the Heijunka + Kanban scheduling has proved to be an excellent "physical" declination of the same concepts postulated by TOC ; we can say a "tailored suit" that fits the Toyota environment. A model that allowed to manage a medium-low variety environment, against the low variety of the Ford type lines. And so many car manufacturers, characterized by a similar operating context, have chosen Lean.

Lean works extremely well up to the moment that product variety and demand is relatively stable. But what happens if we change the production environment?

if we move from a medium low to very high variety of products ?

if we move from high in average to low in average volumes for each reference?

if from a relatively stable demand we switch to really erratic and lumpy demand with strong variations between the different SKUs?

if we move from stable routings to a mess of routings and cycles?

if we move from products with relatively long life cycle to products with short life cycle, with designs constantly updated for new variants / customizations?

We are essentially describing a typical MTO and ETO environment with tons of highly customized item. In this case, the physical rules of Lean (based on supermarkets and kanban containers) become a weakness. In this type of context, Lean struggles to achieve the same amazing results:

First of all the complexity of pre-sizing the system when there are strong fluctuations in demand.

If the products have a short cycle, it is necessary to consider the average long design and stabilization times of the system.

With a plurality of routings it becomes difficult to position all the various supermarkets in a stable way.

It is clear that in such a context, the approach with dynamic time buffers is much more flexible and quicker to adjust according to demand, and therefore makes such an environment certainly more suitable for a pure TOC S-DBR or DBR implementation, or for a DDMRP as well. Are we surprised that some Tier 1 OES in the Automotive segment - in this period of very high demand fluctuation, and due to the increase in variety of products - are switching to TOC concepts as DBR or to the TOC derived DDMRP?

And what about project management contexts? From Lean it has been derived the agile model, a model that however - from personal experience - I have never seen lead to great results on due dates attainment. On the contrary, I have found myself several times correcting the trajectories of projects managed in an agile logic, bringing them back on track by adding to the sprint logic the much more solid logic of TOC CCPM.

If we have defined Lean as an excellent tailor-made suit, we can define TOC as a "very elegant model" from which, once the tissue has been chosen, a great suit can be tailored for each body, so that it can be applied to any process, as its algorithm is completely holistic.

It's a matter of "Accents"

Accents in music are able to change a poor melody into a great one. The same thing is when comparing TOC and Lean. If they both plays the music of flow optimization, accents are set differently on the notes.

As explained, Lean places a strong emphasis on reducing waste, while TOC places its emphasis on maximizing throughput: two very opposite trajectories that, from a strategic point of view, have a big difference.

Lean, by encouraging the "hunt for waste", tends to encourage operations to reduce operating expenses. And in fact in the Western Economies, such representation of Lean has prevailed, the lean thinking to minimize operating costs, driven by the distorted representation of reality provided by Product Costing: when producing in small batches to facilitate the flow, the accounting cost of product tends to grow, and so here is the push to look for additional operational efficiencies to counteract the growth of product cost (an exercise that TOC experts know well to be completely futile, and that moreover Ohno himself admitted that he had to fight all his life against cost accountants to implement Lean).

TOC, by encouraging "Throughput", tends to focus initiatives aimed at increasing the ability to generate income faster than the rate of operating expenses. TOC starting from the assumption that the objective of a company is to make more profits now and in the future, relegates the search for efficiency as a third objective after the maximization of Throughput and the reduction of inventory.

Two observations:

The reduction of expenses is, necessarily, limited. Its limit is zero, but the company will bankrupt long before this limit is reached.

The maximization of throughput, on the other hands, does not have limits other than the constraints. Exploit, subordinate and elevate to raise this limit!!

What do we prefer to optimize? To answer, let's think about an hypothetical discussion between two entrepreneurs.....

Luigi: "Hi Marco, what are you doing, pretending not to see me? Our golf game of last week is still burning you".... laughs

Marco: "Come on, you know I let you win, I can't always beat you at everything"... he laughs in turn...

Luigi: "Don't be a boaster for your "small company". Do you know that this year my company has reached an average efficiency of 95%?"

Marco: "Interesting Luigi. And how much money have you done?"

Luigi: "More or less 3 million before taxes".

Marco: "Understand.... We made 9, although I have no idea of efficiency.... Come on, I challenge you to golf again this weekend, so you can cheer up a bit".

WeeonD - Specialists in TOC

Organizations enjoying enduring and sustainable prosperity are those succeeding in the Exploitation Of Their Constraints

We help Organizations improving rapidly and consistently their performance, applying the innovative methods of Theory of Constraints

Discover more www.weeond.com

Comments